Ohio State students help with COVID-19 contact tracing

Workers learn valuable skills, support stressed community members

By Denise Blough

As part of his master’s program in environmental health sciences, public health student Ajeet Gill was supposed to spend his summer working with a local nonprofit distributing meals and essential services to vulnerable communities.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, derailing his plans and his chance to receive the associated course credit required to complete his degree.

As Gill (right) and other students across the state and nation searched for alternatives to their summer practicums, internships and clinical experiences, health departments were experiencing the unprecedented challenge of tracing the spread of COVID-19. For Gill, this struggle blossomed into a unique opportunity to assist with contact tracing in Ohio.

As Gill (right) and other students across the state and nation searched for alternatives to their summer practicums, internships and clinical experiences, health departments were experiencing the unprecedented challenge of tracing the spread of COVID-19. For Gill, this struggle blossomed into a unique opportunity to assist with contact tracing in Ohio.

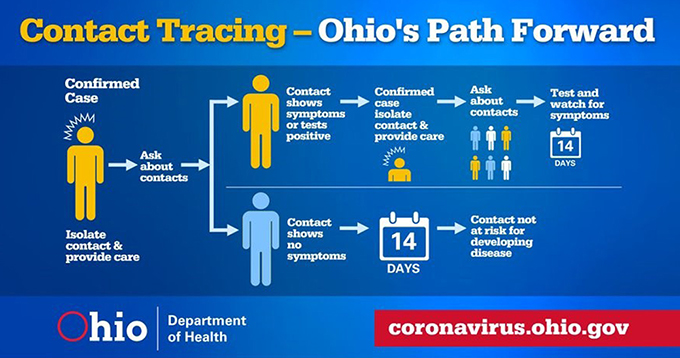

Contact tracing — identifying the web of people who may have come into contact with an infected individual and advising them to self-quarantine — is a task that typically falls on local and state health departments. The decades-old practice tends to be manageable for diseases like measles, tuberculosis and HIV. But with the scale at which COVID-19 was spreading, plus a lack of resources including testing equipment, it wasn’t clear how it was going to work for the pandemic.

“It was recognized pretty early on that the state and local health departments were going to need assistance with contact tracing,” said Bill Miller, senior associate dean of research and professor of epidemiology at the College of Public Health.

Despite talks of contact-tracing apps, traditional calls and texts are still the most reliable and trusted form of monitoring infectious disease spread, he said.

When the state began searching for more contact tracers, college students like Gill were among the first to know. In May, Columbus Public Health hired him as a COVID-19 contact tracer.

In addition to students like Gill who are paid, dozens of Ohio State students and faculty members are part of the Ohio Department of Health’s volunteer pool called the Public Health Assist Team, which local health departments can tap into for COVID-related needs. They come from the Colleges of Arts and Sciences, Medicine and Public Health, among others.

Similar to his original summer project, Gill’s new role allows him to provide a critical public service while he acquires necessary academic experience. His days begin when he receives a list of names and phone numbers to contact that day — sometimes up to 20. His responsibilities are to alert each person of their possible exposure without revealing the identity of the infected individual, inquire about COVID-19 symptoms and health care access, confirm basic demographic information and provide follow-up resources about the virus and benefits of quarantining.

“People are a little apprehensive at first. It takes a lot of social skills to feel out the situation and speak to each person individually in a different way that you think would make them feel comfortable,” Gill said, adding that his involvement in diversity and inclusion organizations around campus has equipped him to comfortably address people of various backgrounds.

“This is a hard job in that you have to be prepared to repeatedly talk to people who are very stressed and very scared,” Miller said. “You have to be comfortable helping those people stay calm and explaining the complex disease quickly and simply.”

In March, an initial call for contact tracing volunteers yielded around 1,200 applications, including more than 900 students from 27 academic institutions, said Joanne Pearsol, deputy director of the Ohio Department of Health. While the newly funded contact tracing workforce has offset some of the need for volunteers, some have been deployed and may be again if surges become overwhelming, said Pearsol, a former staff member at the College of Public Health.

“I grossly underestimated the interest in volunteering, so it was extremely heartening to see that response,” she said. “Not only was it students looking for credit for their coursework, it was other students who were home for the summer. It was professionals who were retired or not working and wanting to contribute in some way.”

Beyond the calls and text messages required to monitor the spread of COVID-19, contact tracing also involves data — a lot of it, said Kara Galvan, a second-year Master of Public Health in epidemiology student who’s working for Columbus Public Health as a data entry specialist.

The work “becomes a little tedious, but it is really for the health of our community,” said Galvan, who plans to get a PhD in epidemiology after her master’s. “Even though my interest lies more with chronic disease, this is still an incredible opportunity.”

Both Galvan and Gill need 120 hours to complete their practicums, but both said they plan to work the full 480 hours at which their temporary positions are capped.

“The contact tracing workforce is an increasingly important public health response as the governor and others are committed to reopening,” said Teresa Long, special advisor for community engagement and partnership at the College of Public Health.

And it hasn’t been an easy task to get up and running. With a planned 1,000-plus new contact tracers in Ohio, it’s been all-hands-on-deck to set up employee resources and training, said Austin Oslock, a student at the College of Medicine and Spring 2020 alum of the College of Public Health who was hired to coordinate the state’s contact tracing training efforts in March. In his role, Oslock has helped shape an eight-hour training course required before state contact tracers can get to work.

“A big part of it is comfort and familiarity with interviews. A lot of our contact tracers come from the medical and public health fields, and many can speak another language,” he said. “Whether you’re telling someone that they have coronavirus or that they may have been exposed to it — those are tough conversations.”

For the students involved, Long said this experience will be foundational and likely set a framework for what students will want to learn more about and how they will be active and thoughtful into their futures.

“There are so many fundamental lessons to be learned about the science, about fairness and justice, about who’s at risk and who’s vulnerable and about how to collectively support everyone.”

About The Ohio State University College of Public Health

The Ohio State University College of Public Health is a leader in educating students, creating new knowledge through research, and improving the livelihoods and well-being of people in Ohio and beyond. The College's divisions include biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health behavior and health promotion, and health services management and policy. It is ranked 22nd among all colleges and programs of public health in the nation, and first in Ohio, by U.S. News and World Report. Its specialty programs are also considered among the best in the country. The MHA program is ranked 5th and the health policy and management specialty is ranked 21st.