Charlottesville police chief talks racism, need to ‘regrow’ policing

RaShall Brackney details challenges, opportunities for law enforcement

By Denise Blough

Police Chief Rashall Brackney of Charlottesville, Virginia has long been an advocate for uprooting police culture.

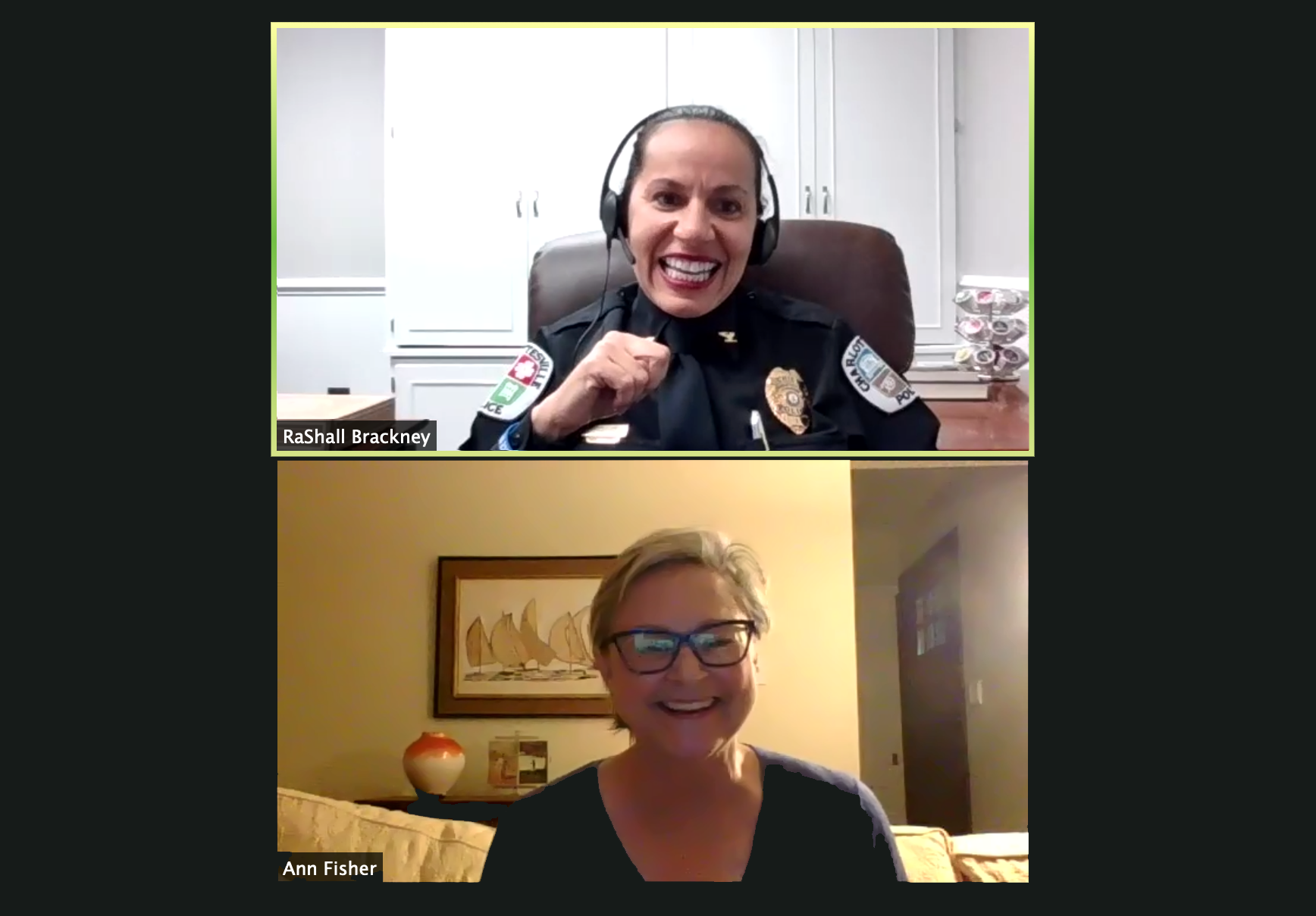

“When you start to look at those persons who are affected [by police], they are the least likely to have access to the internal systems,” said Brackney, who on Nov. 17 joined the College of Public Health for a virtual discussion with WOSU radio host Ann Fisher. The event, “The Bruising of America: When Black, White and Blue Collide,” was the first in Dean Amy Fairchild’s Changing the Conversation: Public Health Thought Leader Series.

Police serving disproportionately poor, minority communities are often not reflective of those populations “in terms of variables and demographics, but also not reflective of the lived experiences of the community,” said Brackney, a 30-year veteran of the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police and former chief of police at George Washington University.

Her virtual talk at Ohio State used the lenses of public health and history to examine inequities that permeate U.S. policing and to explore how to rebuild the system to better serve communities.

A Black woman in a field dominated by white men, Brackney underscored the underrepresentation of Black police officers in the U.S. — only around 3% of the nation’s 800,000-some police professionals. She also explored the origins of policing in the south, which included Black Codes and slave patrols, and the north, where police were often used to break up labor unions.

Police "have always been used as a very divisive arm of government … not as a peacekeeping entity, but a maintaining of systems,” Brackney said, emphasizing that, as an extension of government, police are technically given their authority by the people they serve.

“We’ve created this us-versus-them mentality … so the community doubts us,” she said. “They doubt that we are there to serve, and our actions don’t always align with our words and mottos, as we know from the death of George Floyd.”

Brackney said it’s been critical to try and understand what creates a healthy relationship between a community and its police department by asking community members questions such as how they define harm and safety.

“We haven’t come to a clear understanding of what we want in the U.S. as a policing model, because we’ve never been able to create the model for ourselves. It was handed to us built off of institutional legacies,” Brackney said.

When asked about civilian review boards for police departments — which have been formed in both Columbus and Charlottesville — she said a lack of trust on both sides can pose challenges, but she believes that every police agency has a responsibility to work with these groups and be transparent.

Brackney said she doesn’t plan on giving up her efforts to reform and diversify U.S. policing any time soon.

“I have been very fortunate to be in this profession for 37 years. I’ve had experiences that I would have never thought. I grew up very poor, inner city, one of six kids,” she said. “What’s next for me is where I’m led to. I am on a mission to reform police culture.”

A 37-year police veteran, Brackney joined the Charlottesville Police Department in 2018 following fallout from the 2017 Unite the Right rally. She was the first Black woman to nationally oversee a special operations division and was selected by the U.S. Department of Justice to address bias-based and hate crimes reporting challenges. She’s an expert in harm reduction, procedural and restorative justice and community-police relations, and holds a bachelor’s and master’s from Carnegie-Mellon University and a PhD from Robert Morris University.

About The Ohio State University College of Public Health

The Ohio State University College of Public Health is a leader in educating students, creating new knowledge through research, and improving the livelihoods and well-being of people in Ohio and beyond. The College's divisions include biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health behavior and health promotion, and health services management and policy. It is ranked 22nd among all colleges and programs of public health in the nation, and first in Ohio, by U.S. News and World Report. Its specialty programs are also considered among the best in the country. The MHA program is ranked 5th and the health policy and management specialty is ranked 21st.