Understanding mental health disparities among sexual minorities

Harvard’s Mark Hatzenbuehler explores link between structural stigma, LGBT health

By Denise Blough

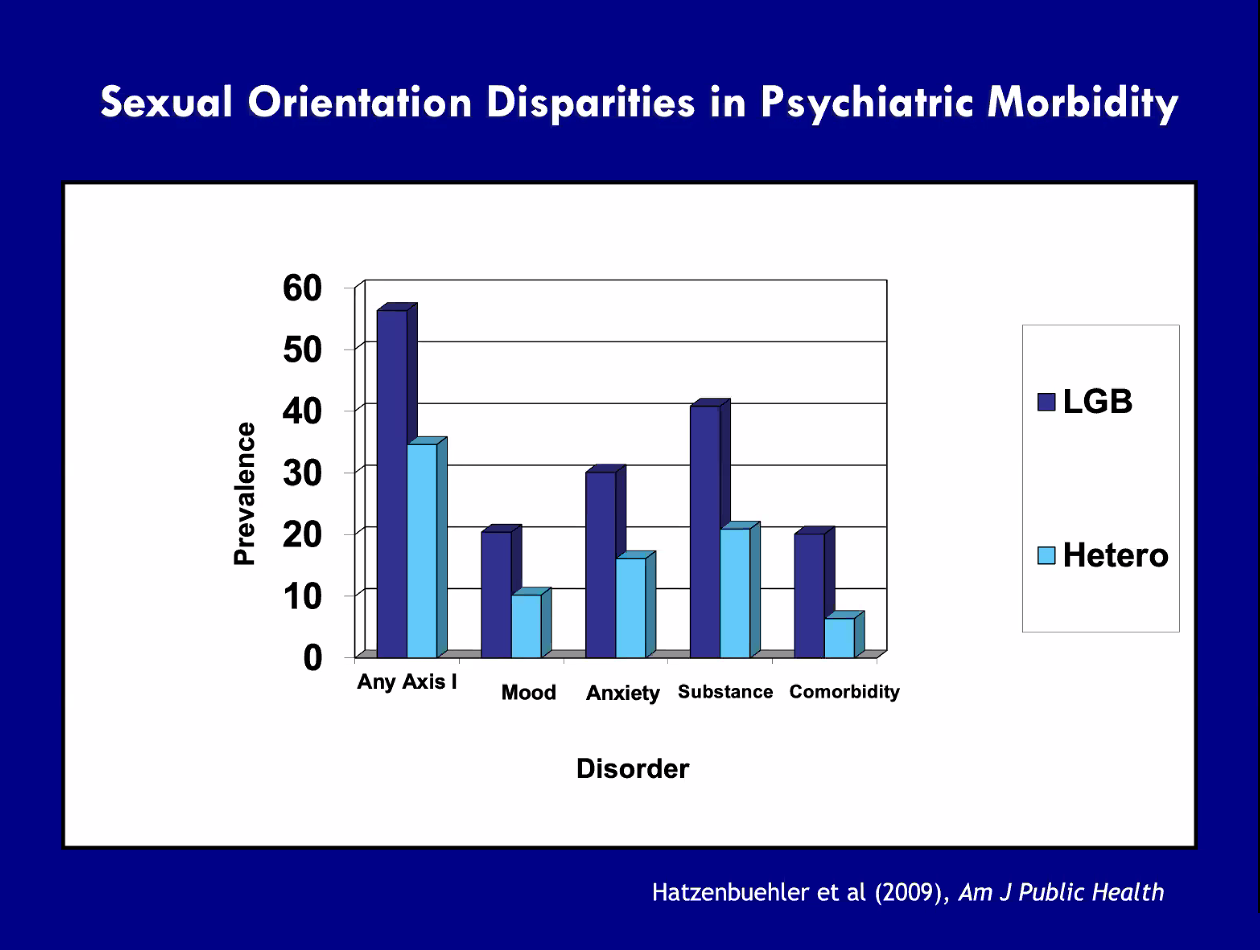

Lesbian, gay and bisexual youth are about twice as likely to report suicidal thoughts than their heterosexual peers, and more than three times as likely to have attempted suicide. Later in life, sexual minorities are more likely to report mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression and substance abuse, said Mark Hatzenbuehler, professor of social sciences at Harvard University.

On Feb. 18, Hatzenbuehler joined the College of Public Health and fourth-year student Marissa Mariner of Student Advocates for Sexual Health Awareness for a webinar to discuss these striking disparities and how they might be linked to structural stigmas at the state and national levels.

“Stigma is one of the most frequently hypothesized risk factors for explaining LGBT mental health disparities,” said Hatzenbuehler, an expert on adverse mental health outcomes among minority groups.

Many researchers have examined the health impacts of individual and interpersonal stigmas — including internalized and perceived stigma, microaggressions and hate crimes — but there’s been a lack of studies pertaining to the impacts of broader, societal-level stigmas on sexual minorities, Hatzenbuehler said.

Over the past decade, he and his colleagues have begun to address this gap in understanding by examining how cultural norms and institutional policies might affect the mental health of LGBT populations. They’ve looked at the distribution of hate crime laws, employer non-discrimination policies and same-sex marriage bans before the 2015 federal ruling that rendered the bans unconstitutional.

Their statistical analyses have suggested that LGBT residents in states with no protective policies are much more likely than heterosexual residents and LGBT residents in states with such policies to experience mental health disorders including depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

“Our work and the work of many others shows the importance of social policy and that social policies are really health policies,” Hatzenbuehler said.

In the future, his team hopes to explore whether and how societal stigmas undermine the effectiveness of mental health interventions for sexual minorities. Improved data collection related to gender identity by government agencies will expand the possibilities for this field of research, he said.

“There also seems to be more openness and willingness in discussing mental health in general,” Hatzenbuehler said.

About The Ohio State University College of Public Health

The Ohio State University College of Public Health is a leader in educating students, creating new knowledge through research, and improving the livelihoods and well-being of people in Ohio and beyond. The College's divisions include biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health behavior and health promotion, and health services management and policy. It is ranked 22nd among all colleges and programs of public health in the nation, and first in Ohio, by U.S. News and World Report. Its specialty programs are also considered among the best in the country. The MHA program is ranked 5th and the health policy and management specialty is ranked 21st.