Ohio State faculty members Maria Gallo, Alison Norris, William Miller and Marcel Yotebieng

Assessing how to build a hospital for mothers and children in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Deciphering why syphilis rates in the U.S. have skyrocketed.

Creating an accurate measure of contraceptive use among Vietnamese women.

Different parts of the world, same shared purpose: understand the needs and barriers, and find answers that lead to better reproductive and sexual health for individuals and populations.

DARING GREATLY IN AFGHANISTAN

“The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again . . . who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

— President Theodore Roosevelt, 1910

Lee Hilling has never kept company with “cold and timid souls.”

During the Vietnam War, he helped lead a team of Navy doctors and corpsmen caring for a civilian population in the Mekong Delta on the Cambodian border. Tough duty, but one that planted the seed for his decades-long drive to improve lives in some of the most challenging places on the planet.

“Although we were a Navy team, we lived with a U.S. Army Special Forces unit,” recounts Hilling, MS ‘74. “They provided our security, but we were accountable to the U.S. Agency for International Development. I saw the desperate state of civilians, especially women and children, during times of war. I met many people who had worked in similar situations all around the world. I decided I wanted to do that too, but I had to wait many years – until I finished my career with the Navy and had a brief health administration career in the U.S. – before I finally had the opportunity.”

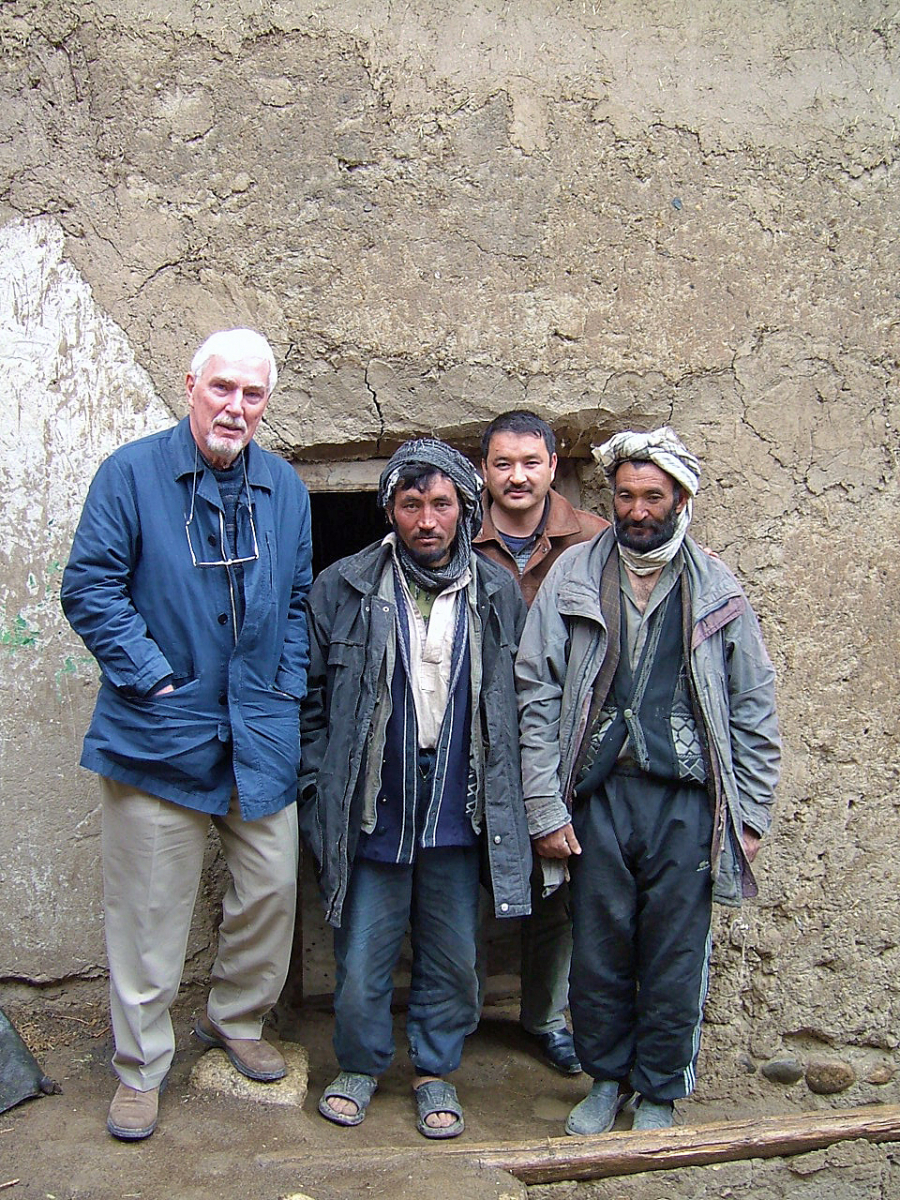

Hilling with village health workers in Bamyan District, Afghanistan.

That opportunity arrived in 1992 when Hilling joined the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), moving with his wife to Karachi, Pakistan, where he was CEO of the Aga Khan University Hospital for six years. The AKDN then tapped Hilling’s combination of health administration leadership and compassion to elevate health systems and care in Pakistan, India, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Tajikistan and now, in Afghanistan.

“My work in Afghanistan, with what eventually became the French Medical Institute for Mothers and Children (FMIC), initially an 85-bed children’s hospital, began in June 2004,” Hilling says. “I was asked by His Highness the Aga Khan to go to Kabul, on behalf of the AKDN, and assess an opportunity to enter into a partnership with the French development organization, La Chaîne de l’Espoir. La Chaîne was building a hospital in Kabul and they realized they needed a long-term partner. Based on my assessment and recommendation, His Highness decided to pursue the partnership.

“I participated in negotiations of an MOU for a public-private partnership, comprised of two private parties – the AKDN and La Chaîne and two public partners – the Governments of Afghanistan and France, with the AKDN managing the institution on behalf of all the partners. I led implementation of the FMIC, and have served as chairman of its board ever since,” says Hilling.

In 2016, an additional 66 beds were opened at the FMIC, including 52 beds for high-risk maternity care and 14 neonatal intensive care beds.

“When asked to go to Afghanistan, I jumped on it,” says Hilling, author of the book, “A Place of Miracles,” which shares the story of the FMIC’s important work. “The horrendous civil war was raging there when we lived next door in Pakistan. We visited an International Commission of the Red Cross (ICRC) hospital on the Afghan border and my hospital treated Afghan refugees and trained Afghan nurses who worked at the ICRC hospital. I had great respect and empathy for them. I have now been to Afghanistan about 70 times, and my respect for and friendship with Afghans has only strengthened by working closely with them for the past 13 years.”

With children in traditional Afghan dress at FMIC's 10th Anniversary celebration.

Hilling says Ohio State provided the foundation for him to be successful in highly unstable environments.

“I was not a traditional student when I entered Ohio State’s health administration program,” says Hilling. “I was 33 years old, married and had four kids. I had a lot of work experience and had served in Vietnam. Despite all that, everyone welcomed me. They prepared me for a successful career in the dynamic U.S. health care environment. I chose to work in the international setting, ultimately in some of the most troubled areas of the world. My Ohio State education and experience enabled me to do that and for that, I will be forever grateful.”

BRIDGES TO BETTER SEXUAL HEALTH

Spend a few minutes with JaNelle Ricks, DrPH, MPA, and you quickly see what makes her effective. A calm demeanor, bright smile, and compassionate focus help her build trust within communities struggling to overcome the complex barriers to better health.

An assistant professor of health behavior and health promotion, Ricks’ expertise plays an indispensable role in sexual health studies, particularly in helping recruit hard-to-reach populations in order to better understand and define a problem, design a comprehensive study, and come up with solutions.

Researcher JaNelle Ricks leads engagement with community partners, such as Equitas Health in Columbus, to recruit men to participate in sexual health studies.

Ricks’s formative research is particularly germane to studies examining HIV/STI prevention and treatment, such as her work in an NIH-funded study exploring the high HIV rates found among minority men who have sex with men (MSM) in Jackson, Mississippi. Jackson has the nation’s highest rate – 40 percent -- of MSM living with HIV.

“My current research addresses sexual and reproductive health issues among adolescent and young adult, racial and ethnic and sexual minority populations,” says Ricks. “I look at the intersection of individual, social and environmental determinants of health, with particular emphasis on health disparities.

“The Jackson study is part of a larger NIH study examining young African-American men and what interventions may help,” says Ricks. “We’re looking at the roles sexual debut, financial imbalance in a relationship and internalized homophobia play, and how disclosure of STI and HIV status to a partner may be affected because of stigma, particularly in the Deep South.”

Ricks is also part of a team working on a new $1.589 million grant from the CDC to examine the reasons for the skyrocketing syphilis rates in Columbus and across the country. Joining Ricks in the study are faculty members William Miller, MD, PhD, MPH, chair of the College of Public Health’s Division of Epidemiology, Abigail Norris Turner, PhD, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the College of Medicine and CPH associate professor of epidemiology, and Julia Applegate, MPH ’17, health program director at the Equitas Health Institute for LGBTQ Health Equity, based in Columbus.

Ricks is working with Equitas Health and Columbus Public Health on community engagement and in developing approaches to recruit a diverse cohort of men to participate in the study.

“Our collaboration with Columbus Public Health and Equitas Health on this project is essential, and will help build a sustainable research partnership,” Miller says.

FORGING TOOLS TO BOOST FAMILY PLANNING

Malawi and the United States mirror each other in some important ways.

“Our group studies why women and couples who don’t want to have a baby sometimes don’t use family planning methods,” says Alison Norris, MD, PhD, assistant professor of epidemiology. “When couples don’t use family planning, women are much more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy. About 40 percent of all pregnancies in Malawi, where we’re doing our study, are unplanned. In the United States, the same proportion – 40 percent of all pregnancies – are unplanned. Unplanned pregnancy is an issue that is experienced everywhere in the world.”

Community members of Wachi village meet with Norris.

A Grand Challenges Explorations award from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is helping Norris develop new tools to improve family planning, whether in Malawi or Ohio.

“The funding from the Gates Foundation can help us understand the barriers to family planning use. We will use our results to design a tool for clinicians and community health workers to guide women and couples with the goal of preventing unplanned pregnancies,” explains Norris. “You might be surprised at the similarities between Malawi and the US in terms of barriers to using family planning. What we learn in Malawi will be useful to improving care and health outcomes for underserved communities here. When pregnancies are planned, women and the infants tend to be healthier than when pregnancies are unplanned.

“For example, we know that very close birth spacing is an important risk for pre-term birth, which is a leading cause of infant mortality in Ohio. This Gates Foundation grant is an investment in our ability to provide better services, leading to better health, for women and families in Malawi and around the world, including right here at home,” says Norris.

Norris’ research examines sexual and reproductive health with a goal of preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and improving reproductive outcomes for women and men.

“I want to understand how context, such as endemic disease, social norms, demographic factors, and cultural and institutional structures, influences health and disease,” Norris says. “Methodologically, I focus on using innovative methods to obtain high-quality data about sensitive and stigmatized topics.”

Norris with UTHA research team members in Malawi village.

An ideal platform for complex research

Not long after arriving at Ohio State in 2012, Norris launched a research program in Malawi called Umoyo wa Thanzi (UTHA), which means “Health for Life” in the Chichewa language.

The Umoyo wa Thanzi team has been working on community and clinic-based projects in collaboration with the non-governmental organization, Child Legacy International (CLI), in Malawi. The CLI organization provides direct community access for researchers and continuity through their daily operations in the areas around Malawi.

The UTHA partnership aims to understand how women’s and men’s decision-making impacts fertility, family planning, pregnancy, and childbirth, as well as HIV and STI testing and treatment.

“With the funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and multiple Ohio State grants, we have carried out three waves of a longitudinal study in a cluster-randomized sample of more than 1,000 reproductive-aged women and their partners,” says Norris, who is also an assistant professor in the College of Medicine. “We are assessing barriers and facilitators to contraceptive use among UTHA cohort participants. This research partnership and community cohort serve as an ideal platform for investigating complex sexual and reproductive health research questions.”

The UTHA study site is based at the McGuire Wellness Centre, a health facility founded by Child Legacy International. Located in the district of Lilongwe in central Malawi, the clinic serves a catchment area of 68 villages (~20,000 people) and provides clinical exam rooms, laboratory space, and accommodations for researchers.

The structure of the UTHA has become a model for the development of sustainable partnerships between universities and non-governmental organizations.

In the future, the ongoing partnership between Ohio State, CLI, and the University of Malawi College of Medicine will be focusing on designing culturally acceptable interventions, based on research, to improve the health of people in Malawi.

“I love my research team,” says Norris. “The Malawians on the team are creative, thoughtful, hardworking and committed. We have a great time designing research studies and implementing them together.”

CREATING MODEL HIV CARE IN THE CONGO

“Some of the challenges that I see in the Congo remind me of my youth growing up in rural Cameroon,” says Marcel Yotebieng, MD, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of epidemiology.

“The limited or difficult access to basic commodities, water, electricity, or sanitation,” Yotebieng says. “The same challenges accessing health care and outcomes. You see children dying at home from preventable diseases like malaria because families cannot afford to take them to the health care center or they take them there when it’s too late.

“Even when they get there, the life-saving medication might not be available.”

Marcel Yotebieng with a family during a home visit in Maluka, DRC. Ashley Ray, BSPH '16, MPH '17, also worked with Yotebieng as a student to conduct a longitudinal analysis of data which examined optimal feeding practices for HIV-positive mothers in the DRC.

Yotebieng’s commitment to finding answers and improving health in low-resource regions has been the propelling force behind his work with collaborators to develop strong research infrastructures in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in other central Africa countries.

His work has informed national and international guidelines on tuberculosis management and treatment of HIV in children. He is currently leading a large cluster trial involving 104 health facilities from the 35 health districts of the province of Kinshasa, DR Congo, with plans to enroll 3,000 HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women and their HIV-exposed infants and follow them for multiple years.

Since 2004, with funding from the NIH, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), WHO, CDC, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Yotebieng and his research team in the Democratic Republic of Congo have worked with the Ministry of Health and other organizations to develop and test best models for scaling HIV care.

“Working with a team of over 80 Congolese collaborators, we successfully engaged key community organizations which together control most of the health care infrastructures in the country --- to directly provide quality HIV prevention, care, and treatment in almost 200 health clinics,” Yotebieng says. “We have identified key barriers to access and use of health services in DRC, proposed and evaluated solutions, and worked with the Ministry of Health to implement at scale for the benefit of the national community. One example of this win-win partnership is in the work to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT).

“We also designed a mother-infant registry to collect real-time data on uptake of critical prevention services,” he says. “With this registry, we learned that the most pressing issue was a high rate of ‘loss to follow-up’ patients. In consultation with the ministry we developed numerous interventions to address this problem including a financial incentive intervention.

“The registry is now being used by the Ministry of Health throughout the nation to monitor PMTCT implementation and to gain an understanding of the long-term programmatic and clinical outcomes among mothers and infants receiving HIV care in maternal and child health clinics in Kinshasa.”

CONCEIVING MEASURES TO IMPROVE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

By the time the speaker finished talking to her fourth-grade class, the career wheels were already churning.

“A Peace Corps volunteer spoke to us about her experiences in Bolivia, helping people sell plants and coffee as part of a micro-business,” says Maria Gallo, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology.

“I decided that day I was joining the Peace Corps.”

Gallo made good on that grade school pledge, serving in the Peace Corps in Nicaragua from 1995-1997. It was also then in a small village in Nicaragua where Gallo witnessed that people fell ill with a “mysterious hemorrhagic fever.” Until a team from the CDC arrived and identified the outbreak of leptospirosis, the cause was unknown.

Gallo says that “seeing a field investigation unfold in real life was powerful.”

Maria Gallo with health care team at Hanoi hospital.

The public health “bug” implanted, Gallo would go on to work in Bardstown, Kentucky, educating migrant farmworkers about health services, helping communities organize, and interpreting in clinics.

“That was like the Peace Corps, but in the US,” says Gallo. “I was attracted to public health because it dealt with inequalities and you were able to see what was happening on the ground.”

After taking her first graduate school course in epidemiology, she found the perfect fit.

“I just love epi,” says Gallo. “You use concrete quantitative skills and also can work with people and on issues on the ground. In public health, we think based on making the system better, and epi is essential to population health.”

For the past 16 years, Gallo has conducted research, primarily in low-resource settings, with the “overarching goal to influence public health, clinical practice, and individual behavior in order to improve women and men’s reproductive health.”

Her research, which includes an NIH RO1-funded trial in Thanh Hoa, Vietnam, and a study inKingston, Jamaicato “debunk myths about contraceptive safety among women,” focuses on understanding, measuring, and preventing risky sexual behavior and related outcomes, such as HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, unexpected pregnancies, and unsafe abortions.

Gallo’s work in Vietnam received a boost this summer when she received a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges Explorations Award. The funding supports her research to “adapt a validated computer-based psychological test known as the Implicit Association Test to measure the implicit opinions of women in Vietnam on hormonal contraceptives in order to encourage use.”

Much of Gallo’s work has been centered on developing semen biomarkers as objective measures for sexual exposure. These biomarkers revealed to Gallo and her team that women might not be able to give good accounts of their exposure to unprotected sex. She and her team were not surprised by these findings and Gallo says that, “it is critical that we improve our research on sensitive topics by developing ways of measuring that don’t rely on self-reports.”

With the Gates award, Gallo begins a new project that will build off of her previous research, extending a validated computer-based psychological test—the Implicit Association Test (IAT)—to collect implicit measures of beliefs about contraceptive safety and naturalness.” The IAT is available online and is used to measure racial prejudices.

According to Gallo, the IAT is used in social psychology as an implicit measure of the association between two constructs and has proved useful in research concerning attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. It is helpful when people may be hesitant or unable to report their true feelings.

Using the IAT to objectively measure women’s beliefs could “improve both clinical care to women and the quality of research methodology in the field of contraception,” says Gallo.

Health educator in Vietnam counsels a couple on contraceptive options.