Young alumna experiences public health at full throttle

COVID-19 puts Kate Wright ’20’s career on the fast track

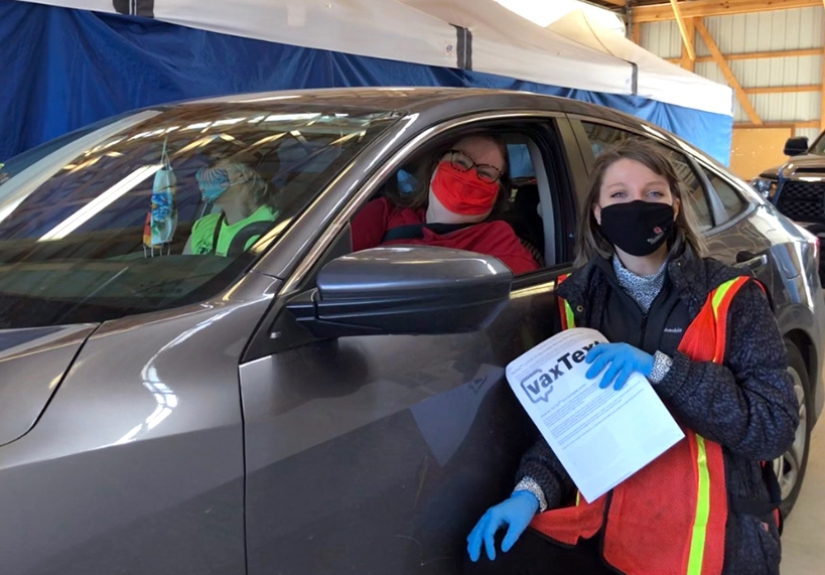

Kate Wright (right) works at a drive-through vaccine clinic for her job as an epidemiologist for Union County Health Department

Wake up. Drive 45 minutes to work. Throw on a mask and rubber gloves to administer COVID-19 tests and vaccines. Clean up and investigate positive cases. Correspond with local schools about new diagnoses. Distribute test results. Share data with the state.

Is it time for lunch yet?

It wasn’t always clear what Kate Wright MPH ’20 wanted to do with her career, but she definitely couldn’t have foreseen being thrown straight into a pandemic upon graduation. As an epidemiologist for Union County Health Department, Wright spent the last two years navigating the complexities and high-pressure demands of local public health’s response to COVID-19.

Since joining Union County in summer 2020, she’s investigated COVID cases, been certified to administer COVID tests and vaccines, scheduled test/vaccine clinics, corresponded with state and local partners, managed test kit distribution and much more.

“Our health department has 45 employees, so it was all-hands-on-deck,” she said, adding that the normal day-to-day operations of the department became secondary to the pressing needs of protecting the community.

“While it was a lot to handle just starting a job, I was relieved to finally be helping to educate people — It was a big change (from being in school), and I felt helpful.”

“While it was a lot to handle just starting a job, I was relieved to finally be helping to educate people — It was a big change (from being in school), and I felt helpful.”

The county’s relatively small health department — which serves about 62,000 residents, compared to Columbus’ nearly 1 million — means Wright also had opportunities to take on leadership roles withiin her team, including becoming the dedicated epidemiologist liaison for Union County Schools. As part of this role, she helped build the online reporting systems the schools use to report COVID cases.

“Case reporting has been incredibly difficult during the pandemic, especially for our schools, and so these online forms really helped us capture where we were surging and what mitigation strategies might be working,” Wright said.

She’s also been charged with analyzing data for Fayette, Crawford, Hardin and Wyandotte Counties, which have fewer (or no) epidemiologists on staff.

“People in small health departments have had to be incredibly resourceful and creative throughout the pandemic,” said Dr. Teresa Long, former health commissioner for Columbus Public Health and special advisor of community engagement and partnership at the College of Public Health.

Long said it’s this small-but-mighty approach to running local health departments is common, and a characteristic that led many people from urban areas to flock to rural ones when the COVID vaccine was first available in 2021. In some cases, smaller health departments were the quickest and most efficient at setting up clinics, she said.

Long said she relates to Wright’s experience in many ways, given her own journey working at the San Francisco Health Department during the beginning of the AIDS/HIV epidemic in the 1980s.

“There were these same challenges of not knowing — the science wasn’t there, and there was a lot of fear and stigma,” Long said.

Wright said that misinformation has been the biggest challenge of her job, and she’s had to learn how to effectively communicate with people who have different ideas about the virus.

“At the end of the day, these are your community members — I may not be directly connected to someone, but I am here in this role to help explain what we know from a public health perspective. It’s important to be empathetic, diplomatic and have compassion,” Wright said, adding that when people threaten to sue or make hateful remarks, “you just separate yourself from the interaction and follow the proper steps.”

When COVID numbers have been low, she’s had the opportunity to learn the ins and outs of the health department’s usual priorities, which include offering immunization and wellness clinics, analyzing trends in communicable diseases (such as sexually transmitted infections), overseeing the Union County Overdose Prevention and Fatality Review Coalition and conducting food inspections.

Despite the ups and downs of her job, Wright said having the opportunity to contribute in the midst of a pandemic felt like a blessing among all the uncertainty.

“The pandemic hit right when I was about to graduate. I remember applying to dozens of jobs and hearing nothing back. Everything was so up in the air,” she said. “At the same time, I felt a pull — I had just finished a master’s program in epidemiology. I thought, ‘OK, I have the education; I have the tools, now I should put them to use.’”

So, Wright began volunteering her time to COVID efforts, including contact tracing for Fairfield County and preparing test kits at Ohio State, which she did when she wasn’t working at her then-full-time job as a research assistant.

“My education at the College of Public Health helped prepare me for these experiences in many ways,” she said. “Something I hope to carry forward with me would be the indomitable spirit I’ve seen throughout. Whether it was making test kits or educating someone about the vaccine they were about to receive, I was always surrounded by people who… just want to help others by any means possible.”

Long said that Wright’s experience, while unique to the pandemic, is also more broadly representative of the best kind of public health work.

“Public health is a team sport, and there’s a unique spirit about that. There’s always the opportunity to have great impact,” she said.

Public health need and student interest on the rise

- A fall 2021 report by the de Beaumont Foundation and Public Health National Center for Innovation found that the U.S. public health workforce needs to grow by 80% just to provide the minimum level of basic public health services to all Americans. The report found that the biggest need is among local health departments serving fewer than 100,000 people, like Union County.

- In 2021, the Biden-Harris Administration announced $7.4 billion toward revitalizing and supporting the public health workforce, including $3 billion for a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-led grant program to modernize the public health workforce, infrastructure and data systems.